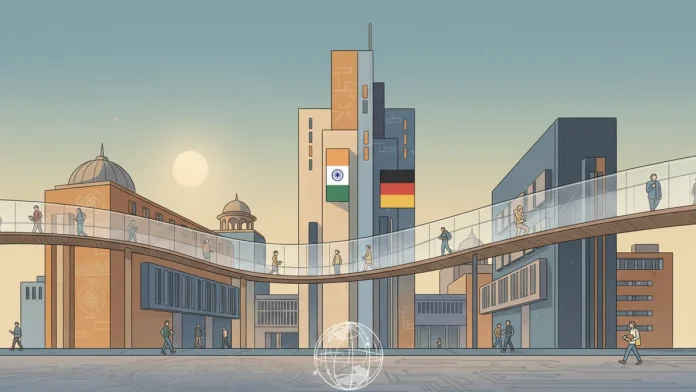

Something shifted quietly during Chancellor Friedrich Merz’s January visit to India. Not in a dramatic handshake way, but in the tone of how higher education was discussed. Universities were no longer a side note to trade or diplomacy. They were the point.

India and Germany’s new higher education roadmap reads less like a polite agreement and more like an invitation to settle in. German universities are being openly encouraged to open campuses in India. Not exchange desks. Not short programmes. Actual, physical institutions. That alone says a lot about where both countries think the future is heading.

On the ground, this matters because it reflects pressure building on both sides. India has an enormous, restless student population.Many students think internationally, but for plenty of them studying abroad is simply out of reach. At the same time, Germany is struggling with skill shortages that its own education system cannot address quickly enough, particularly in engineering, green energy and applied fields.

For Indian students, the change could feel practical rather than ideological. A German degree earned in Delhi, Chennai or Mumbai means fewer visa worries, lower costs and less family disruption. One professor in Bengaluru joked that it could finally make “international education feel local”.At the same time, these campuses are not designed to operate in isolation. Students are still expected to move between countries, spending time in Germany or working within joint research teams.

German universities see something else entirely. India is not just a source of students anymore. It is a research environment, an industry partner, a testing ground. Being present locally allows closer ties with Indian companies, faster collaboration and a better sense of how skills translate into jobs. It is a different model from the old approach of recruiting talent late in the pipeline.

The roadmap also aligns with India’s wider push to reshape higher education. In recent years, foreign universities have been let in more carefully under clearer rules. A few are already up and running, others are still waiting, while cities like Mumbai, Bengaluru and Delhi-NCR are trying to brand themselves as global education hubs, competing not only with one another but with places like Singapore and Dubai.

There are frictions, though. German universities have historically been careful about offshore campuses. Language, staffing and academic control remain sensitive issues. Some academics quietly question whether the German system, deeply tied to public funding and local governance, can adapt easily to a different regulatory culture.

Beyond campuses, the roadmap links education to work in a more explicit way. The planned Indo-German centre for renewable energy skills is a clear signal. Degrees, skills training and industry demands are being pulled closer together, with universities acting as the main connectors. It points to a broader change in higher education, where getting students ready for work is no longer a sensitive topic, but something taken for granted.

There is also a geopolitical undertone, even if no one says it out loud. As global academic partnerships become more fragile, India and Germany are choosing depth over symbolism. Fewer slogans, more structures.

Whether this experiment succeeds will depend on details: fees, access, quality and whether students from less privileged backgrounds actually benefit. But for now, the direction feels clear. Higher education is no longer just about where students go. It is about where universities decide to stay.