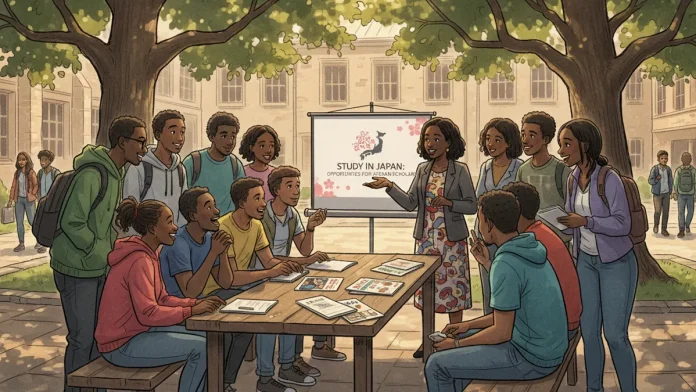

On a warm afternoon at a university campus in Nairobi, a Japanese education official stands under a tree answering questions from students who linger long after the presentation ends. They ask about housing. About language barriers. About whether Japan feels welcoming once the novelty fades. No one mentions rankings. This isn’t that kind of conversation.

Japan is making a deliberate push to attract more students from African countries, and the timing feels telling. While some traditional destinations are becoming harder to access, more expensive, or less predictable, Japan is stepping forward with a different message. Come study. We’ll fund it. Learn skills that travel.

Right now, the numbers are small. Fewer than 2,000 African students are enrolled across Japanese universities. That’s barely visible in a system long dominated by students from China, Vietnam, and Nepal. But officials want that to change. Quietly, recruitment offices are being set up in Kenya and Botswana. Faculty members are being dispatched to build relationships, not just sign agreements.

Part of the motivation is demographic reality. Japanese campuses are feeling emptier each year. The domestic student pool is shrinking, and universities outside major cities feel it first. Africa, meanwhile, is young. Graduation ceremonies there are getting bigger, not smaller. For Japanese institutions facing half-filled lecture halls, the contrast is hard to ignore.

There’s also a sense that African students are looking beyond familiar paths. Europe and North America still attract interest, but visas are tighter, costs are higher, and the process often feels opaque. Japan’s offer is more structured. Scholarships are clear. Pathways are defined. For students focused on engineering, technology, or applied sciences, that clarity matters.

At the same time, the interest isn’t purely transactional. Ask students why Japan, and many talk about culture before curriculum. Anime, gaming, design, manufacturing. Japan feels known, even from far away. That familiarity lowers the psychological barrier. It makes the leap feel possible.

Japanese universities know challenges remain. Language is the obvious one. Daily life can be isolating. Jobs after graduation aren’t guaranteed. Still, partnerships with African universities and professional programmes aim to smooth the transition. Some initiatives are designed with return in mind, encouraging graduates to take skills home rather than stay.

On campuses in Japan, the impact is subtle but noticeable. A few more African accents in seminar rooms. Different perspectives in group projects. Small changes that shift the atmosphere.

Japan’s move isn’t loud, and it isn’t rushed. It feels more like a long bet. One built on the idea that today’s students become tomorrow’s bridges. Whether that bet pays off will depend not just on scholarships or marketing, but on how these students experience life once they arrive. That part can’t be scripted.